Welcome to A People's Atlas of Nuclear Colorado

To experience the full richness of the Atlas, please view on desktop.

Navigating the Atlas

You may browse the Atlas by following the curated "paths" of information and interpretation provided by the editors. These paths roughly track the movement of radioactive materials from the earth, into weapons or energy sources, and then into unmanageable waste—along with the environmental, social, technical, and ethical ramifications of these processes. In addition to the stages of the production process, you may view in sequence the positivist, technocratic version of this story, or the often hidden or repressed shadow side to the industrial processing of nuclear materials.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Kevin Hamilton, U.S. Air Force Academy campus, 25 June 2018, courtesy Kevin Hamilton

Essay

The United States Air Force was born of the nuclear age. Though aircraft had played a key role in two world wars, the United States did not establish the Air Force as a distinct branch of the armed forces until 1947. America had fought World War II on land and at sea, but it was air power that to many had proved decisive in the war, and that air power culminated in the apocalyptic use of atomic power. After the war, the United States aggressively turned to air-atomic forces to establish and maintain control over newly won, globe-wide zones of influence and dominion. Though the Truman administration established the nominally “civilian” Atomic Energy Commission to manage nuclear technology on behalf of the nation, it was the Air Force more than any other institution in the government that controlled and used the technology necessary for weaponizing it.

While the Air Force and the nuclear weaponry it relentlessly wielded were air based, deployment was land based. Like all the lands of the United States, deployment depended on the settlement and occupation of other people’s ground—this time in service of nuclear-weapons experimentation, manufacturing, and operation. From 1948 to 1954 the United States conducted eight above-ground nuclear weapons tests, half in the occupied seascape of the Marshall Islands, and half in the colonized lands of the Shoshone in the state of Nevada.

These tests were not only scientific events. They were rhetorical events, incorporated into the symbolic performances of deterrence, which Hannah Arendt once described as Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 16.“some sort of tentative warfare in which the opponents demonstrate to each other the destructiveness of the weapons in their possession." As such, these toxic spectacles were aggressively photographed and filmed. The images were used as threats. They were also used by the United States to reassure, or at least attempt to reassure, American citizens and America’s international allies that this latest errand of the United States into the wilderness of destruction was legitimate and fully within the competencies of the nation. American nuclear dominance thus depended on the occupation of both land and consciousness.

Such occupations led to a curious preoccupation in the upper ranks of the United Sates Air Force, a preoccupation with its public image. It was as if the apocalyptic assertions of the new military force needed a modern, progressive, futuristic counterstatement. Toward this end, the Air Force summoned not only a myriad of photographic images—most of them shot by a special unit of the Air Force called the 1352nd Photographic Squadron, or Lookout Mountain Laboratory—but also architecture to establish its legitimacy, authority, and modernity.

Image and architecture, as well as colonization and modernity, came together in the controversial founding in 1954 of a major officer training facility, the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Here at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, the Air Force built much more than an educational institution meant to rival West Point or Annapolis: it constructed for itself an iconic monument that, in the words of historian Robert Allen Nauman, assumed the burden of Robert Allen Nauman, On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 1.“symbolically representing both the United States and the Air Force, as well as the philosophical and cultural agendas that defined this country during the cold war.” Robert Allen Nauman, On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 1, 3.This search for "architectural meaning" resulted in a project framed “in mythic terms that related to modernism, flight, and its Colorado site." Of these terms, modernity—specifically, an air-atomic modernity—was essential.

The site, secured in 1954 after numerous bureaucratic and political battles over just where to erect the Air Force’s monument to its modernity, lay just north of Colorado Springs on the eastern slopes of the Rampart Range and beneath majestic Pikes Peak. There it formed an axis point. Seen from the plain to the east, it offered a hollowed gateway to the mythic West, echoing the modernism of the St. Louis Gateway Arch designed in 1947, the year of the Air Force’s founding. Moreover, its perch suggested a clear vantage point from which to look back to the east, and into the settler past. And it was situated on the north-south axis of the “nuclear highway,” the thousand-mile Interstate 25 joining the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico to the missile silos of Wyoming.

Colorado Springs won out over proposed locations in Illinois and Wisconsin. Nauman situates the decision in the context of a broader push to diversify the economies of the American West after World War II. Western states that had enjoyed an unprecedented manufacturing boon during the war were keen to see their economies less dependent on eastern centers of power. The West and Western industry were explicitly identified with "free enterprise and a mythic frontier heritage." That heritage would come through forcefully in architectural and photographic representations of the Academy, tapping into Colorado's historical association with Manifest Destiny and the active cultural present of the Hollywood Western. When completed, the Academy’s first cadets would enter their new monumental home under a line from an 1895 poem by Sam Walter Foss:

Throughout its debut and early history, the new Academy served as a stage for the styling of American modernity in terms of atomic-age aerial might. Expertise in style and staging was crucial here. SOM produced a design drawing from what was widely known as the “International Style,” an approach born largely out of European design in the first part of the 20th century. Characterized by an emphasis on building function over ornamentation, and on the experience of space and light over mass and permanence, this style also often celebrated new technologies and their capabilities. But the Academy’s modernity went beyond building design. The Air Force commissioned Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille to design cadet uniforms, marked by his experience in the staging of elaborate pageantry for screen and stage. It partnered with journalist John Hohenberg, long-time administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, and one of Walt Disney’s chief “imagineers,” Don Edgrin, to design communication campaigns.

In 1959, in time for the arrival of the first cadets on campus, the Air Force established a detachment of Lookout Mountain Laboratory, its preeminent photographic and motion picture studio, on Cascade Avenue in Colorado Springs (later relocated to an outpost at Ent Air Force Base). Officially designated “Detachment 2” of then 1352nd Photographic Squadron, the photographic unit was dedicated to photographically staging the new Air Force Academy against the backdrop of the Rockies—as well as the boring of missile silos in the western plains and the hollowing of Cheyenne Mountain to create an atomic-proof headquarters from which to monitor the continent’s aerial borders and inaugurate a retaliatory nuclear strike. In all of Detachment 2’s work, but especially in documentation of the Academy, Colorado's landscape played a major role as a symbolic resource, an iconographic grounding of air-atomic power in the mythologies and histories of white settlement.

The photographers of Lookout Mountain Laboratory’s Detachment 2 were quite versed in such stories, having begun their work in Oceania creating films and photographs of atomic and nuclear tests that portrayed the nuclear detonations at once as awful necessities and safe experiments. Formed in 1947 out of Operation Crossroads, the first post-war atomic test, Lookout Mountain Laboratory was a self-contained Hollywood film studio with full soundstage, film processing laboratory, and everything else one could wish for in modern cinema. From 1947-1969 Lookout Mountain Laboratory would draw from Hollywood industry expertise to document the Air Force’s most ambitious airborne and earth-shaping projects, supplying both highly stylized representations and specialized visual data to military and civilian clients within the nuclear industrial complex.

Photographers at Lookout Mountain Laboratory’s outpost in Colorado Springs borrowed Walt Disney's eleven-camera Circarama rig to capture a panoramic view of the new facility during graduation week in 1959. The resulting footage was screened as part of Disneyland's Monsanto-sponsored “America the Beautiful” attraction for the next ten years. They shot television episodes at the Academy for both the Bob Hope Show and the Bob Cummings Show. And they filmed presidential visits from Eisenhower to Kennedy, especially for each spring’s photogenic commencement ceremonies.

As such, the new Air Force Academy quickly became a kind of Cold War visual fetish. National Geographic, Time, Life, and the Saturday Evening Post, each featured spreads of the Academy, with subheadings such as “Glass Walls Merge with Mountains,” or “Academy Rises from a Mesa.” Kodak featured the new facility on its famous 60’ x 18’ Colorama billboard, “the world’s largest photograph,” which was hung imposingly above commuters in New York's Grand Central Station. “The camera records our power for peace,” read the caption.

From the design of the Academy’s site and structures through their representation in Air Force films and popular media, Air Force branding accomplishes a definition of modern aerial-atomic might as both utterly technological and as a naturalized extension of a past indebted to the elemental “untamed” landscape of the American West. Nauman and others have pointed to the inherent contradictions of such a rhetorical and ideological project: how does the “international style” square with the creation of a monument to nationalism? How could a structure be “timeless” in its style, as the Air Force claimed, and yet also so responsive to its precarious historical moment? And how can an icon, in the words of SOM designer Walter Netsch, Jory Johnson, "Man as Nature," in Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, ed. Robert Bruegmann (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 104.“compete with [the] infinity” of the landscape itself?

The words of the project’s landscape architect, Dan Kiley, offer one key to how the designers address these tensions and conflicts. “It’s not man and nature,” he is reported to have observed about the site’s design. Rather, “Man is nature.” The Academy’s regular geometries and austere forms may communicate a technological modernity, but they also evoke a simplicity of form that is rooted in the mathematical patterns of “nature.” Floating as they do above the landscape on smaller bases and columns, the dormitory and classroom buildings of the Academy may suggest flight, but they also suggest a graduation from the raw form of seemingly disorganized rock and slope to the purer, inner forms of line, curve, and volume.

Tensions abound in SOM’s design. As a collection of modern, hard-edged forms against the backdrop of the craggy Rampart range, the complex evokes iconographies of Western conquest, as in earlier depictions of surveyors and prospectors, marked by their technology as alien to their surroundings. Yet the site also invites experience of the buildings as very much of the landscape, nestled around the mountain’s base, or appearing out of the earth like some version of the rock formations just to the south at the Garden of the Gods.

The building materials—aluminum, glass, concrete—also seem both of and not-of the landscape. Their visual purity and simplicity again evoke the elemental nature of the Rockies, as if more recently unearthed through glacial or even volcanic change. Meanwhile, their relative novelty as structural architectural components remind us of their origins in utterly modern processes of refinement and production.

Creation of a Monument, a 1956 film produced by Lookout Mountain Laboratory about the site’s construction, draws on some of these representational tensions, strategies, and themes. The film’s music-accompanied title scenes of dirt pushed closer to the camera by a bulldozer fade to a sequence of the Academy’s first class at their temporary location outside of Denver at Lowry Field, watching a jet fly overhead on its way south to survey their future home. Creation of a Monument spends surprisingly little time on the designs for the buildings themselves, instead offering ample scenes of the site portrayed as undisturbed, touched only lightly before by Indians and ranchers. The site is thus presented as everything else is in atomic modernity: as raw material waiting to be processed. Indeed, the filmmakers turn to a sequence of land surveyors, soil samplings, and laboratory tests of soil and building material: this, too, is an experimental site.

In this way, the film presents the Academy like the atomic bomb as not so much as having “tamed” the wild land, made use of it, processed it, refined it. Here human intervention, be it in the form of running atomic tests or building architectural monuments, picks up where the glaciers left off, but with a new modern consciousness of the land’s destined nature.

Depictions of the Air Force against the backdrop of the Colorado Rockies thus depict aerial might as an inevitable extension and fulfillment of the earth’s geologic processes. These same representations also portray land as elemental, and ripe for exploitation. In this way, jets above could seem pure and intractable, while the tracts below could be harvested or spoiled, as needed, in the production of a nuclear modernity.

Hamilton, Kevin and Ned O’Gorman. Lookout America! The Secret Hollywood Studio at the Heart of the Cold War. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth University Press, 2018.

Hamilton, Kevin and Ned O’Gorman. “Seeing Experimental Imperialism in the Nuclear Pacific.” Media+Environment 3, no. 1 (2021).

"History of 1352 Motion Picture Squadron, Lookout Mountain Air Force Station, July 1, 1959–December 31, 1959." February 1, 1960. Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama.

"History of the United States Air Force Academy June 10, 1957–June 11, 1958." McDermott Library, Clark Special Collections Branch, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado.

"History of the United States Air Force Academy, July 1, 1963–June 30, 1964." McDermott Library, Clark Special Collections Branch, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado.

Johnson, Jory. "Man as Nature." In Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, edited by Robert Bruegmann, 102-20. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Nauman, Robert Allan. "Presenting the Academy." In Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, edited by Robert Bruegmann, 121-38. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Nauman, Robert Allen. On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Rein, Christopher M. “’Men to Match My Mountains’: Environmental Aspects of the U.S. Air Force Academy Site Selection Process." In High Flight: History of U.S. Air Force Academy, edited by Edward A. Kaplan, 57-76. Chicago, IL: Imprint Publications, 2011.

Smith, Jeffery J. Tomorrow’s Air Force. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Witters, Arthur G. “Building the Permanent Site of the U.S. Air Force Academy, 1954–1968." In High Flight: History of U.S. Air Force Academy, edited by Edward A. Kaplan, 107-18. Chicago, IL: Imprint Publications, 2011.

While the Air Force and the nuclear weaponry it relentlessly wielded were air based, deployment was land based. Like all the lands of the United States, deployment depended on the settlement and occupation of other people’s ground—this time in service of nuclear-weapons experimentation, manufacturing, and operation. From 1948 to 1954 the United States conducted eight above-ground nuclear weapons tests, half in the occupied seascape of the Marshall Islands, and half in the colonized lands of the Shoshone in the state of Nevada.

Christopher Rosenberger, Air Force Academy T-38 Thunderbird, 22 February 2018, Flickr

These tests were not only scientific events. They were rhetorical events, incorporated into the symbolic performances of deterrence, which Hannah Arendt once described as Hannah Arendt, On Revolution (New York: Penguin Books, 1991), 16.“some sort of tentative warfare in which the opponents demonstrate to each other the destructiveness of the weapons in their possession." As such, these toxic spectacles were aggressively photographed and filmed. The images were used as threats. They were also used by the United States to reassure, or at least attempt to reassure, American citizens and America’s international allies that this latest errand of the United States into the wilderness of destruction was legitimate and fully within the competencies of the nation. American nuclear dominance thus depended on the occupation of both land and consciousness.

Such occupations led to a curious preoccupation in the upper ranks of the United Sates Air Force, a preoccupation with its public image. It was as if the apocalyptic assertions of the new military force needed a modern, progressive, futuristic counterstatement. Toward this end, the Air Force summoned not only a myriad of photographic images—most of them shot by a special unit of the Air Force called the 1352nd Photographic Squadron, or Lookout Mountain Laboratory—but also architecture to establish its legitimacy, authority, and modernity.

Image and architecture, as well as colonization and modernity, came together in the controversial founding in 1954 of a major officer training facility, the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Here at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, the Air Force built much more than an educational institution meant to rival West Point or Annapolis: it constructed for itself an iconic monument that, in the words of historian Robert Allen Nauman, assumed the burden of Robert Allen Nauman, On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 1.“symbolically representing both the United States and the Air Force, as well as the philosophical and cultural agendas that defined this country during the cold war.” Robert Allen Nauman, On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 1, 3.This search for "architectural meaning" resulted in a project framed “in mythic terms that related to modernism, flight, and its Colorado site." Of these terms, modernity—specifically, an air-atomic modernity—was essential.

The site, secured in 1954 after numerous bureaucratic and political battles over just where to erect the Air Force’s monument to its modernity, lay just north of Colorado Springs on the eastern slopes of the Rampart Range and beneath majestic Pikes Peak. There it formed an axis point. Seen from the plain to the east, it offered a hollowed gateway to the mythic West, echoing the modernism of the St. Louis Gateway Arch designed in 1947, the year of the Air Force’s founding. Moreover, its perch suggested a clear vantage point from which to look back to the east, and into the settler past. And it was situated on the north-south axis of the “nuclear highway,” the thousand-mile Interstate 25 joining the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico to the missile silos of Wyoming.

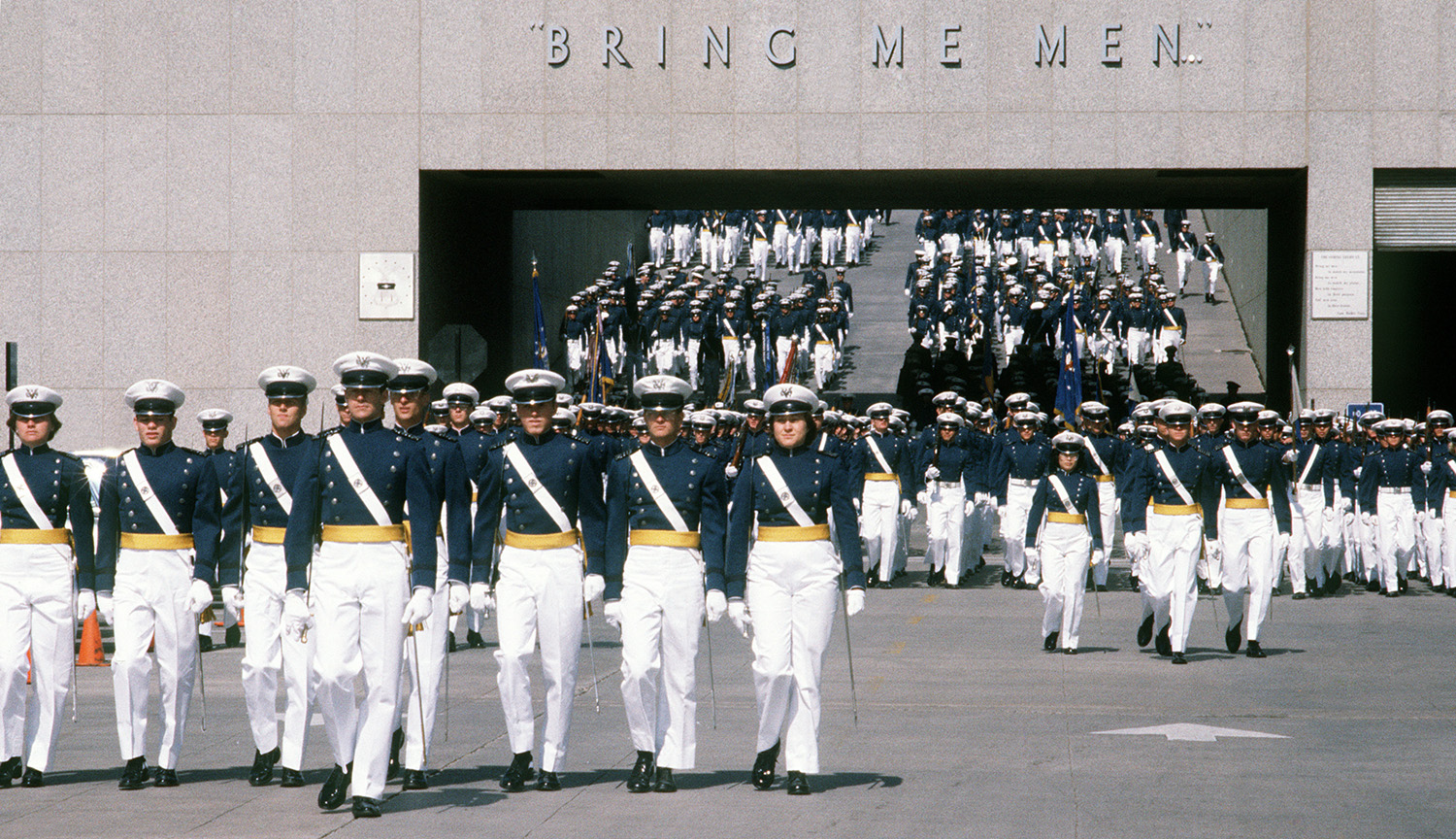

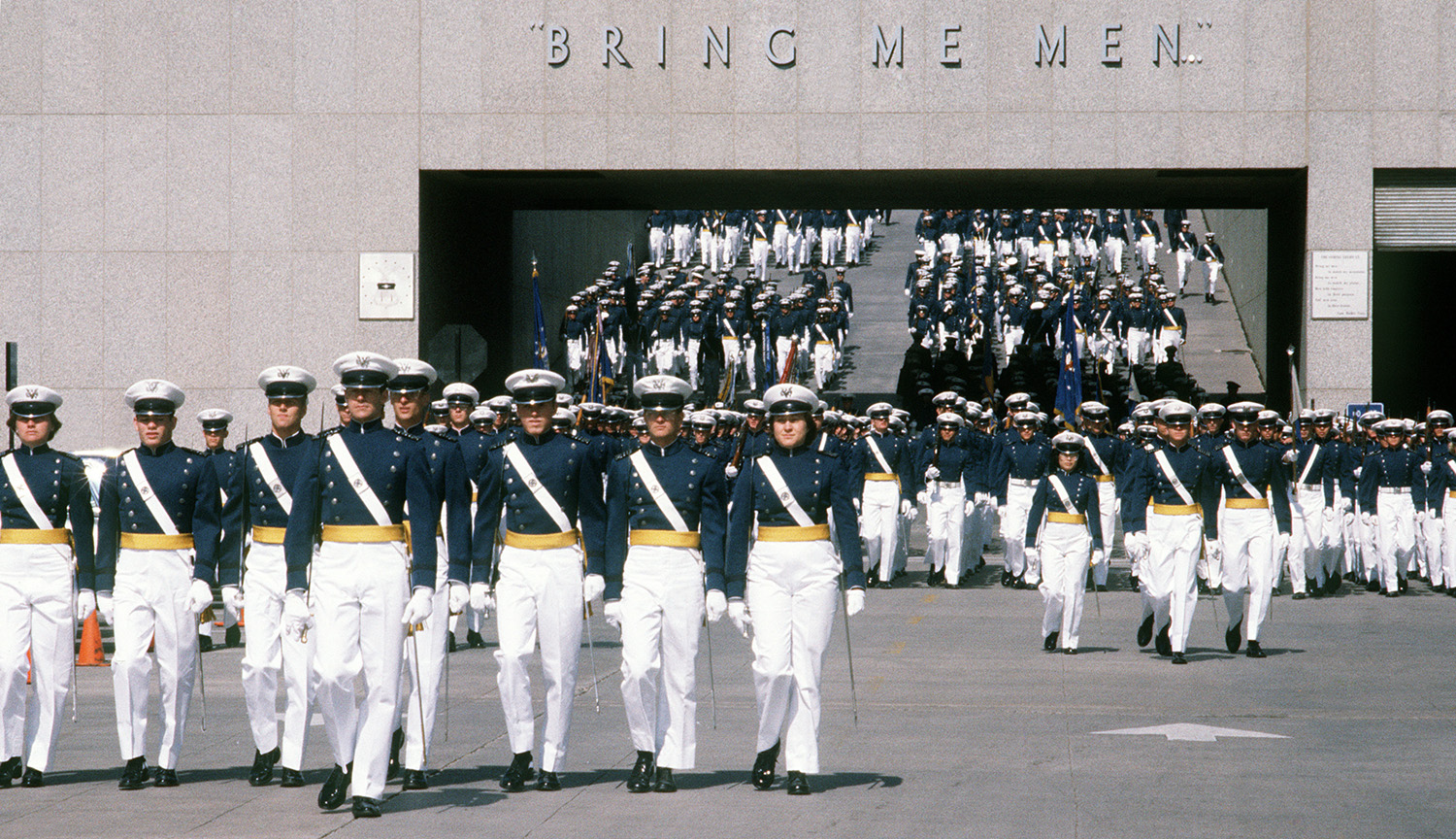

Colorado Springs won out over proposed locations in Illinois and Wisconsin. Nauman situates the decision in the context of a broader push to diversify the economies of the American West after World War II. Western states that had enjoyed an unprecedented manufacturing boon during the war were keen to see their economies less dependent on eastern centers of power. The West and Western industry were explicitly identified with "free enterprise and a mythic frontier heritage." That heritage would come through forcefully in architectural and photographic representations of the Academy, tapping into Colorado's historical association with Manifest Destiny and the active cultural present of the Hollywood Western. When completed, the Academy’s first cadets would enter their new monumental home under a line from an 1895 poem by Sam Walter Foss:

Christopher M. Rein, “'Men to Match My Mountains’: Environmental Aspects of the U.S. Air Force Academy Site Selection Process," in High Flight: History of U.S. Air Force Academy, ed. Edward A. Kaplan (Chicago, IL: Imprint Publications, 2011), 72.Bring me men to match my mountains

Bring me men to match my plains

Men with empires in their purpose

And new eras in their brains

Unknown photographer, Cadet Parade at the U.S. Air Force Academy, cropped from original, 1 January 1984, Records of the Office of the Secretary of Defense, 1921 - 2008, Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982 - 2000

The “new era” came with high pressure and a high price tag. Arthur G. Witters, “Building the Permanent Site of the U.S. Air Force Academy, 1954–1968" in High Flight: History of U.S. Air Force Academy, ed. Edward A. Kaplan (Chicago, IL: Imprint Publications, 2011), 116Commandeering the land alone totaled upwards of $6.5 million. The Air Force’s contract with the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (SOM), would rise from an initial cost of $23,527.50 to many hundreds of thousands more (with Robert Allen Nauman, On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 30, 133.SOM later claiming to have lost as much as $1 million on the effort). SOM was a highly visible engineering and architecture firm whose previous government contracts included the design of the city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee for the Manhattan Project. In spring of 1955, SOM debuted their designs for the Academy at an exhibition at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. For this high-pressure occasion, the architects commissioned an exhibition from Herbert Bayer, a Bauhaus designer who had played a leading role in the Museum of Modern Art's popular "Family of Man" exhibition. Visitors walked through rooms usually dedicated to the Robert Nauman, "Presenting the Academy," in Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, ed. Robert Bruegmann (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 123."Indian Museum," but now transformed into an austere and dramatically-lit series of pastoral vignettes. Models and renderings of the SOM designs for the Academy sat against mural-sized photographs of the site by Ansel Adams.Throughout its debut and early history, the new Academy served as a stage for the styling of American modernity in terms of atomic-age aerial might. Expertise in style and staging was crucial here. SOM produced a design drawing from what was widely known as the “International Style,” an approach born largely out of European design in the first part of the 20th century. Characterized by an emphasis on building function over ornamentation, and on the experience of space and light over mass and permanence, this style also often celebrated new technologies and their capabilities. But the Academy’s modernity went beyond building design. The Air Force commissioned Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille to design cadet uniforms, marked by his experience in the staging of elaborate pageantry for screen and stage. It partnered with journalist John Hohenberg, long-time administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, and one of Walt Disney’s chief “imagineers,” Don Edgrin, to design communication campaigns.

In 1959, in time for the arrival of the first cadets on campus, the Air Force established a detachment of Lookout Mountain Laboratory, its preeminent photographic and motion picture studio, on Cascade Avenue in Colorado Springs (later relocated to an outpost at Ent Air Force Base). Officially designated “Detachment 2” of then 1352nd Photographic Squadron, the photographic unit was dedicated to photographically staging the new Air Force Academy against the backdrop of the Rockies—as well as the boring of missile silos in the western plains and the hollowing of Cheyenne Mountain to create an atomic-proof headquarters from which to monitor the continent’s aerial borders and inaugurate a retaliatory nuclear strike. In all of Detachment 2’s work, but especially in documentation of the Academy, Colorado's landscape played a major role as a symbolic resource, an iconographic grounding of air-atomic power in the mythologies and histories of white settlement.

The photographers of Lookout Mountain Laboratory’s Detachment 2 were quite versed in such stories, having begun their work in Oceania creating films and photographs of atomic and nuclear tests that portrayed the nuclear detonations at once as awful necessities and safe experiments. Formed in 1947 out of Operation Crossroads, the first post-war atomic test, Lookout Mountain Laboratory was a self-contained Hollywood film studio with full soundstage, film processing laboratory, and everything else one could wish for in modern cinema. From 1947-1969 Lookout Mountain Laboratory would draw from Hollywood industry expertise to document the Air Force’s most ambitious airborne and earth-shaping projects, supplying both highly stylized representations and specialized visual data to military and civilian clients within the nuclear industrial complex.

U.S. Air Force, Still from Lookout Mountain Air Force Station briefing film, 1969, National Archives and Records Administration

Photographers at Lookout Mountain Laboratory’s outpost in Colorado Springs borrowed Walt Disney's eleven-camera Circarama rig to capture a panoramic view of the new facility during graduation week in 1959. The resulting footage was screened as part of Disneyland's Monsanto-sponsored “America the Beautiful” attraction for the next ten years. They shot television episodes at the Academy for both the Bob Hope Show and the Bob Cummings Show. And they filmed presidential visits from Eisenhower to Kennedy, especially for each spring’s photogenic commencement ceremonies.

As such, the new Air Force Academy quickly became a kind of Cold War visual fetish. National Geographic, Time, Life, and the Saturday Evening Post, each featured spreads of the Academy, with subheadings such as “Glass Walls Merge with Mountains,” or “Academy Rises from a Mesa.” Kodak featured the new facility on its famous 60’ x 18’ Colorama billboard, “the world’s largest photograph,” which was hung imposingly above commuters in New York's Grand Central Station. “The camera records our power for peace,” read the caption.

From the design of the Academy’s site and structures through their representation in Air Force films and popular media, Air Force branding accomplishes a definition of modern aerial-atomic might as both utterly technological and as a naturalized extension of a past indebted to the elemental “untamed” landscape of the American West. Nauman and others have pointed to the inherent contradictions of such a rhetorical and ideological project: how does the “international style” square with the creation of a monument to nationalism? How could a structure be “timeless” in its style, as the Air Force claimed, and yet also so responsive to its precarious historical moment? And how can an icon, in the words of SOM designer Walter Netsch, Jory Johnson, "Man as Nature," in Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, ed. Robert Bruegmann (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 104.“compete with [the] infinity” of the landscape itself?

Mike Kaplan, New cadets salute at their first formation at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, 26 June 2009, U.S. Air Force

The words of the project’s landscape architect, Dan Kiley, offer one key to how the designers address these tensions and conflicts. “It’s not man and nature,” he is reported to have observed about the site’s design. Rather, “Man is nature.” The Academy’s regular geometries and austere forms may communicate a technological modernity, but they also evoke a simplicity of form that is rooted in the mathematical patterns of “nature.” Floating as they do above the landscape on smaller bases and columns, the dormitory and classroom buildings of the Academy may suggest flight, but they also suggest a graduation from the raw form of seemingly disorganized rock and slope to the purer, inner forms of line, curve, and volume.

Tensions abound in SOM’s design. As a collection of modern, hard-edged forms against the backdrop of the craggy Rampart range, the complex evokes iconographies of Western conquest, as in earlier depictions of surveyors and prospectors, marked by their technology as alien to their surroundings. Yet the site also invites experience of the buildings as very much of the landscape, nestled around the mountain’s base, or appearing out of the earth like some version of the rock formations just to the south at the Garden of the Gods.

The building materials—aluminum, glass, concrete—also seem both of and not-of the landscape. Their visual purity and simplicity again evoke the elemental nature of the Rockies, as if more recently unearthed through glacial or even volcanic change. Meanwhile, their relative novelty as structural architectural components remind us of their origins in utterly modern processes of refinement and production.

Creation of a Monument, a 1956 film produced by Lookout Mountain Laboratory about the site’s construction, draws on some of these representational tensions, strategies, and themes. The film’s music-accompanied title scenes of dirt pushed closer to the camera by a bulldozer fade to a sequence of the Academy’s first class at their temporary location outside of Denver at Lowry Field, watching a jet fly overhead on its way south to survey their future home. Creation of a Monument spends surprisingly little time on the designs for the buildings themselves, instead offering ample scenes of the site portrayed as undisturbed, touched only lightly before by Indians and ranchers. The site is thus presented as everything else is in atomic modernity: as raw material waiting to be processed. Indeed, the filmmakers turn to a sequence of land surveyors, soil samplings, and laboratory tests of soil and building material: this, too, is an experimental site.

In this way, the film presents the Academy like the atomic bomb as not so much as having “tamed” the wild land, made use of it, processed it, refined it. Here human intervention, be it in the form of running atomic tests or building architectural monuments, picks up where the glaciers left off, but with a new modern consciousness of the land’s destined nature.

Depictions of the Air Force against the backdrop of the Colorado Rockies thus depict aerial might as an inevitable extension and fulfillment of the earth’s geologic processes. These same representations also portray land as elemental, and ripe for exploitation. In this way, jets above could seem pure and intractable, while the tracts below could be harvested or spoiled, as needed, in the production of a nuclear modernity.

Sources

Arendt, Hannah. On Revolution. New York: Penguin Books, 1991.Hamilton, Kevin and Ned O’Gorman. Lookout America! The Secret Hollywood Studio at the Heart of the Cold War. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth University Press, 2018.

Hamilton, Kevin and Ned O’Gorman. “Seeing Experimental Imperialism in the Nuclear Pacific.” Media+Environment 3, no. 1 (2021).

"History of 1352 Motion Picture Squadron, Lookout Mountain Air Force Station, July 1, 1959–December 31, 1959." February 1, 1960. Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama.

"History of the United States Air Force Academy June 10, 1957–June 11, 1958." McDermott Library, Clark Special Collections Branch, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado.

"History of the United States Air Force Academy, July 1, 1963–June 30, 1964." McDermott Library, Clark Special Collections Branch, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado.

Johnson, Jory. "Man as Nature." In Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, edited by Robert Bruegmann, 102-20. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Nauman, Robert Allan. "Presenting the Academy." In Modernism at Mid-Century: The Architecture of the United States Air Force Academy, edited by Robert Bruegmann, 121-38. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Nauman, Robert Allen. On the Wings of Modernism: The United States Air Force Academy. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Rein, Christopher M. “’Men to Match My Mountains’: Environmental Aspects of the U.S. Air Force Academy Site Selection Process." In High Flight: History of U.S. Air Force Academy, edited by Edward A. Kaplan, 57-76. Chicago, IL: Imprint Publications, 2011.

Smith, Jeffery J. Tomorrow’s Air Force. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Witters, Arthur G. “Building the Permanent Site of the U.S. Air Force Academy, 1954–1968." In High Flight: History of U.S. Air Force Academy, edited by Edward A. Kaplan, 107-18. Chicago, IL: Imprint Publications, 2011.

Continue on "Legacies"