Welcome to A People's Atlas of Nuclear Colorado

To experience the full richness of the Atlas, please view on desktop.

Navigating the Atlas

You may browse the Atlas by following the curated "paths" of information and interpretation provided by the editors. These paths roughly track the movement of radioactive materials from the earth, into weapons or energy sources, and then into unmanageable waste—along with the environmental, social, technical, and ethical ramifications of these processes. In addition to the stages of the production process, you may view in sequence the positivist, technocratic version of this story, or the often hidden or repressed shadow side to the industrial processing of nuclear materials.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Phil LaCombe, Fallout Shelter Sign in Brattleboro, VT, 2009, Flickr

Issue Brief

The Cold War was a time of international and domestic tension under the threat of nuclear war, with lasting impacts on the cultures of numerous countries, including the United States. In 1949, the first successful test of a Soviet atomic weapon put Americans on the edge of their seats about atomic warfare. The U.S. government began to exhort the American public to build home and commercial shelters as early as 1955, and the advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles in 1958 accelerated the construction of personal fallout shelters in case the tension between countries led to the deployment of nuclear missiles. By 1965 an estimated 200,000 fallout shelters dotted the American landscape. Family, community, and government fallout shelters served as domestic vehicles of U.S. military preparedness against nuclear threat. By the late 1970s, Cold War tensions began to diminish, and fallout shelter culture slipped out of the commonplace. Yet a half century later, many Cold War shelters still exist as physical reminders of international tension, domestic mobilization, and the instability of national and global environmental futures.

Despite the promotion of building home fallout shelters, the federal government was aware that these shelters, by and large, would not withstand a nuclear blast. If nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union occurred, the U.S. government recognized that the most likely outcome would be mutually assured destruction, and in most cases the home fallout shelter would not save lives. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.Thus, civil defense was more a method of boosting the morale of the population on the “home front” than a means of actually securing physical safety in the event of a blast. Shelters and shelter culture during the Cold War were a primary means to enlist the American public to perform rituals of citizenship for their country out of patriotic duty.

The culture surrounding Cold War fallout shelters advocated a highly gendered division of labor depicted in idealized images of white “nuclear family” households of the American suburbs. Men were charged with creating and securing a safe and hardened space to protect the family in case of a nuclear attack, and women were tasked with stocking shelters with food and necessities for first aid, comfort, and survival. This served as both a reminder and a source of hope for Americans that family life would continue to exist in the events following an atomic blast. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.Children played their role as well: they were trained in duck and cover techniques in school and were to dutifully inform their families of threats and help them prepare. Fear of nuclear attack would be met with familial duty and civic responsibility to overcome national insecurity through domestic defense.

Government promotion of the building and stocking of shelters galvanized family consumption and participation in the growth of the war-time economy. Businesses across the nation specially marketed their building materials, generators, furniture, survival gear, and food products to exploit nuclear fears. Many hardware and department stores set up entire displays consisting of the necessary goods to build or stock a home shelter. Civil defense plans suggested that at minimum a seven to fourteen-day supply of food and water be kept in fallout shelters and supermarkets. Food brands created and marketed specific fallout shelter foodstuffs, such as crackers and canned water.

The media supported this wartime propaganda by averring that Americans could survive a nuclear war by escaping to underground bunkers. A constant stream of newspaper articles and periodicals reminded the American public of the current status of the Cold War conflict and how best to prepare for the uncertain future. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 20.Anthropologist Joseph Masco has observed that underground shelter was marketed as the new American frontier. Nothing was more authentically American than being prepared on all fronts for a “Red” nuclear attack and being able to survive in this underground secured territory, “where the resilient citizen could outwit a dangerous world with grit, skill, and moral determination.” With roots in the romanticized ideal of the settler-colonial foundations of the nation—the “Wild West” and the American dream—the underground frontier of the bunker as a means of survival appealed to many Americans, who believed independence and resilience in the face of threat were core American values.

Promoting the survivability of nuclear war in fallout shelters was the public face of a far more thorough shelter effort to construct hardened facilities for military technologies and resources. In 1959, Cheyenne Mountain, outside of Colorado Springs, Colorado, was selected to house the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), the collaborative U.S.-Canada organization that provides aerospace warning, air sovereignty, and protection for North America. The location deep inside the Cheyenne Mountain Complex would protect NORAD’s system of computers in case of a nuclear strike. The burrowed complex remains one of the most famous icons of the Cold War in Colorado.

The National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program, implemented by the Kennedy Administration in 1961, funded an extensive survey of buildings to determine suitable shelter placement. Local governments hired local architectural and engineering companies to assess buildings in order to determine the feasibility of constructing public fallout shelter locations. These locations were then mapped, marked by signs and in community shelter plans, and occasionally stocked with survival supplies. Nathan Heffel, "Not That You'll Need Them, But You Can Still Spot Some of Denver's Fallout Shelters," Colorado Public Radio, August 15, 2017, http://www.cpr.org/show-segment/not-that-youll-need-them-but-you-can-still-spot-some-of-denvers-fallout-shelters/.A partnership between the federal government and state and local government agencies helped to maintain and keep records of these facilities.

The Denver Metropolitan area was one of the earliest communities in the country to plan community fallout shelters, and was well ahead of many cities when the Kennedy Administration implemented national measures for shelter establishment. Beginning in the early 1950s, the city developed a comprehensive civil defense plan and conducted an expansive survey of community buildings that identified 116 shelters. Thirteen of these shelters were stocked with food, water, blankets, and other survival supplies. Two prominent locations were the Denver City and County building, which could provide shelter for over 2,500 people, and the YMCA on Yale Avenue and Colorado Boulevard. Kathryn Plimpton, “The Forgotten Cold War: The National Fallout Shelter Survey and the Establishment of Public Shelters,” Master’s Thesis, Historic Preservation Program, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, April 24, 2015, https://digital.auraria.edu/work/ns/996bae38-fad0-4c85-b443-d7aceec21816.By 1964 the city of Denver had designated enough locations to provide shelter for over 900,000 people; 334 of these structures were officially demarcated with signage. Sarah Magnuson, “A Brief (and Bleak) History of Building Fallout Shelters in American Homes,” Apartment Therapy, July 10, 2020, https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/fallout-shelters-american-homes-36770210.Shelter buildings were made of stone, brick, or concrete and had the ability to hold 50-150 people for a duration of two weeks. More than 200 of Denver’s marked shelters were located in the downtown area. The number of suburban home family shelters built during this period, however, is poorly documented and difficult to estimate owing to a lack of historic records. Outside of Denver, the city of Golden identified 15 public shelters in existing buildings through the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program, and Arapahoe County similarly identified 6 shelters.

Media portrayals romanticize these shelters in war games and nostalgic memories of new American frontiers and patriotic duty. In reality, many shelters were little more than stark basements with few stocked food items or medical kits and only minimally suited to protect occupants from immediate post-blast fallout. In the event of a nuclear blast on the Front Range, shelter safety and effectiveness would have been hampered by poor access, uncertain supply lines, and lack of protection from radioactive fallout over substantial periods of time. Today, the lasting legacy of these shelters can be seen in the myriad household storage areas filled with forgotten boxes and the tattered remnant yellow and black signs on metropolitan buildings that point to basements long converted to other uses. Many family shelters were dismantled in the years following the relaxation of Cold War tensions; basement shelters were commonly repurposed or removed and filled in to promote safety.

Heffel, Nathan. "Not That You'll Need Them, But You Can Still Spot Some of Denver's Fallout Shelters." Colorado Public Radio, August 15, 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Klara, Robert. “Cold War Nuclear Fallout Shelters Were Never Going to Work.” History.com, October 16, 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Magnuson, Sarah. “A Brief (and Bleak) History of Building Fallout Shelters in American Homes.” Apartment Therapy, July 10, 2020. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Masco, Joseph. "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society." Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Plimpton, Kathryn. “The Forgotten Cold War: The National Fallout Shelter Survey and the Establishment of Public Shelters.” Master’s Thesis, Historic Preservation Program, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, April 24, 2015. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Scoles, Sarah. “A Rare Journey into the Cheyenne Mountain Complex, a Super-Bunker That Can Survive Anything.” Wired, May 3, 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020.

“This Is Why Cheyenne Mountain Is One of the Most Secure Bases in the US.” Airman Magazine, July 23, 2020. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Nuclear Fear and Family Culture

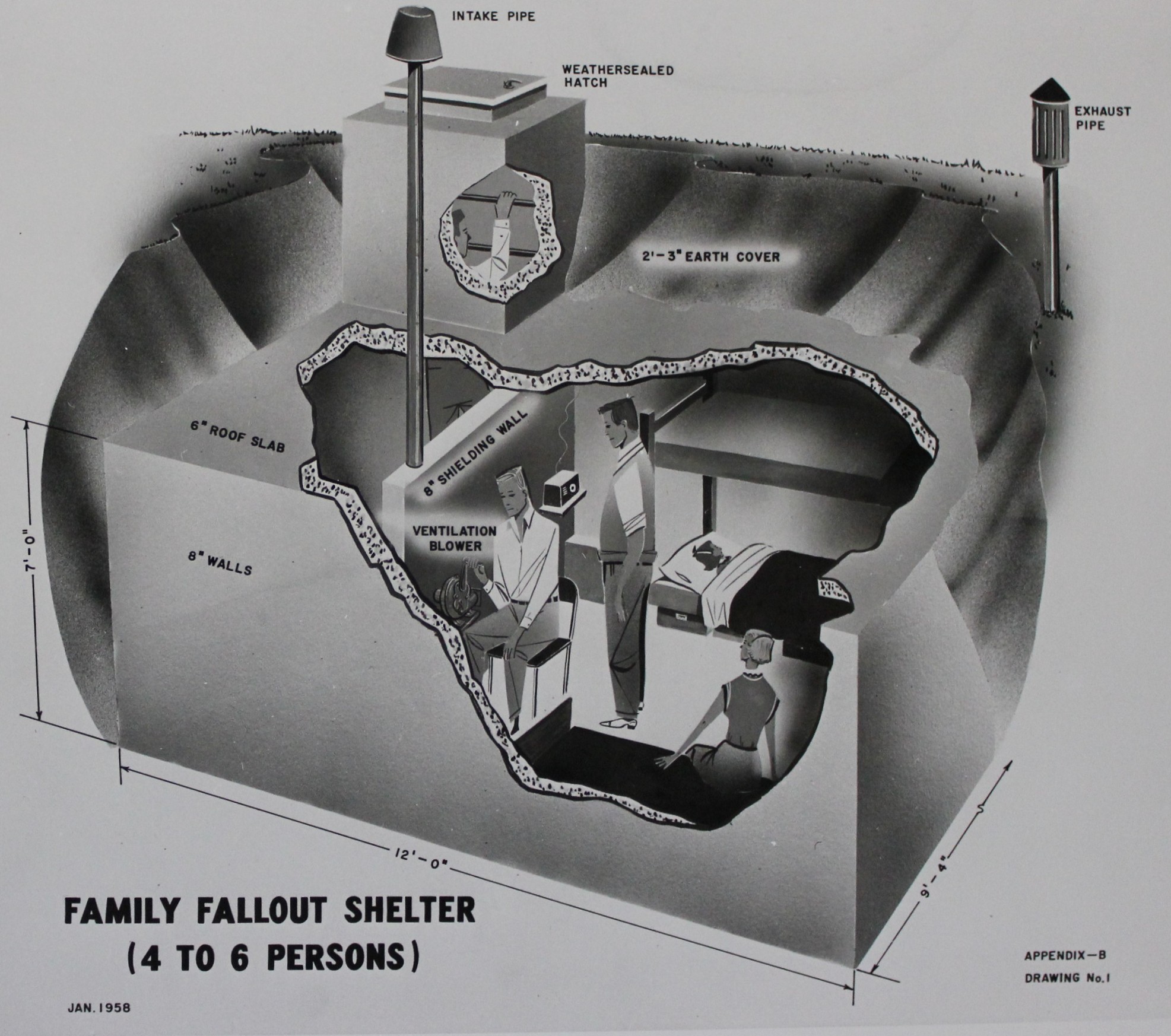

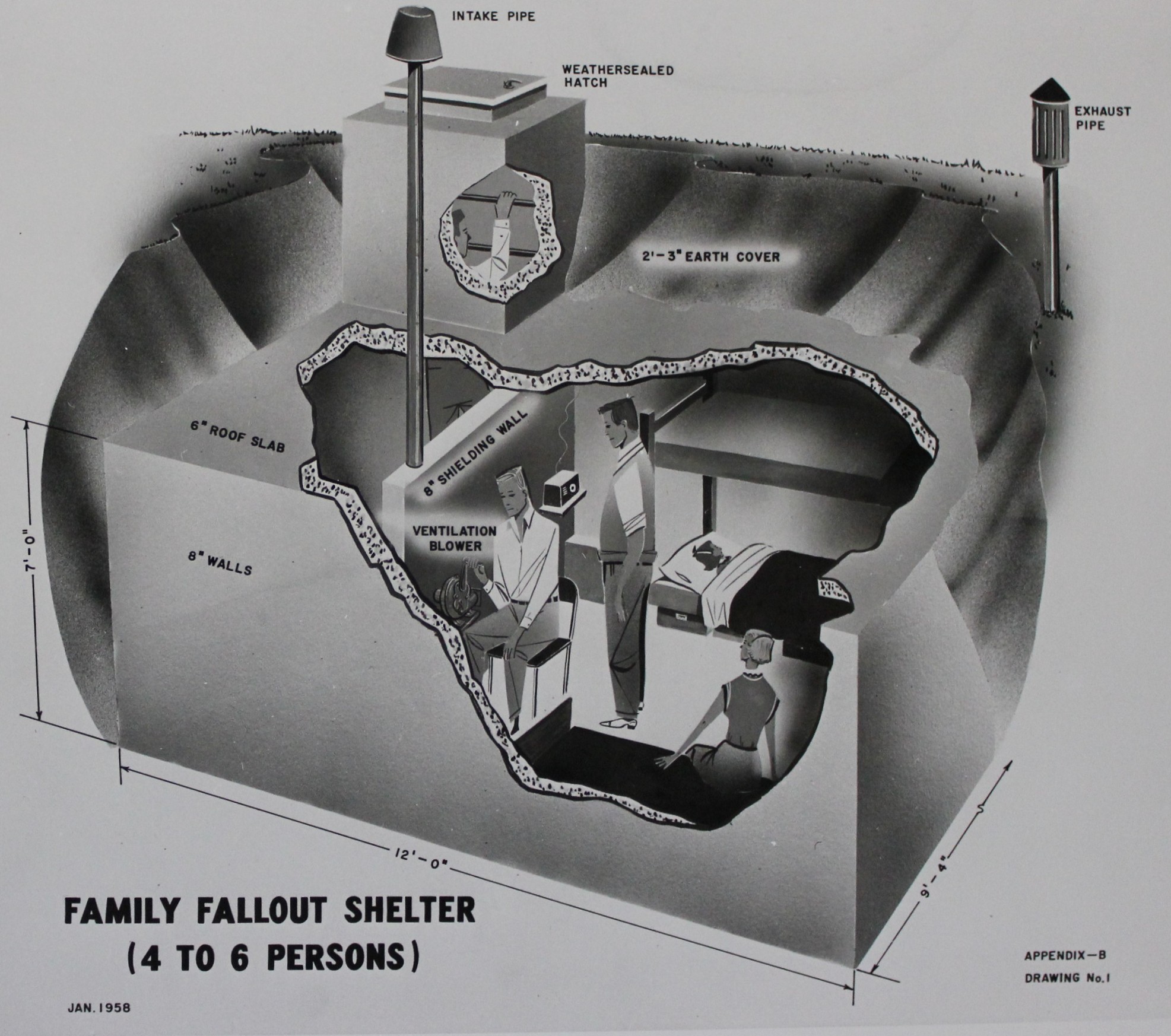

Beginning in the late 1940s and peaking in the 1950s and 1960s, the fear of nuclear war profoundly impacted American culture and made preparation for survival an everyday consideration. State-backed wartime consumerism both fueled and sought to contain this fear by encouraging the stockpiling of resources in the face of imminent attack. Civil defense mobilized the masses to support the wartime economy and exhibit patriotism through domestic preparedness and fortification. In this context, many citizens constructed home fallout shelters and stocked them with survival equipment and supplies. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.The government promoted the installation of such shelters, channeling fear and anxiety into projects that were patriotic and viewed at the time as economically and culturally productive. With private contractors and the federal government developing and distributing various fallout shelter construction plans, Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.these militarized home-based protection units took many forms, customized to fit a variety of locations and made out of different materials in order to cater to the individual spaces and financial challenges of American families.

Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization. Region 1, A diagram of a Family Fallout Shelter for four to six persons, 1958, National Archives and Records Administration

Despite the promotion of building home fallout shelters, the federal government was aware that these shelters, by and large, would not withstand a nuclear blast. If nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union occurred, the U.S. government recognized that the most likely outcome would be mutually assured destruction, and in most cases the home fallout shelter would not save lives. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.Thus, civil defense was more a method of boosting the morale of the population on the “home front” than a means of actually securing physical safety in the event of a blast. Shelters and shelter culture during the Cold War were a primary means to enlist the American public to perform rituals of citizenship for their country out of patriotic duty.

The culture surrounding Cold War fallout shelters advocated a highly gendered division of labor depicted in idealized images of white “nuclear family” households of the American suburbs. Men were charged with creating and securing a safe and hardened space to protect the family in case of a nuclear attack, and women were tasked with stocking shelters with food and necessities for first aid, comfort, and survival. This served as both a reminder and a source of hope for Americans that family life would continue to exist in the events following an atomic blast. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29.Children played their role as well: they were trained in duck and cover techniques in school and were to dutifully inform their families of threats and help them prepare. Fear of nuclear attack would be met with familial duty and civic responsibility to overcome national insecurity through domestic defense.

Government promotion of the building and stocking of shelters galvanized family consumption and participation in the growth of the war-time economy. Businesses across the nation specially marketed their building materials, generators, furniture, survival gear, and food products to exploit nuclear fears. Many hardware and department stores set up entire displays consisting of the necessary goods to build or stock a home shelter. Civil defense plans suggested that at minimum a seven to fourteen-day supply of food and water be kept in fallout shelters and supermarkets. Food brands created and marketed specific fallout shelter foodstuffs, such as crackers and canned water.

The media supported this wartime propaganda by averring that Americans could survive a nuclear war by escaping to underground bunkers. A constant stream of newspaper articles and periodicals reminded the American public of the current status of the Cold War conflict and how best to prepare for the uncertain future. Joseph Masco, "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society," Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 20.Anthropologist Joseph Masco has observed that underground shelter was marketed as the new American frontier. Nothing was more authentically American than being prepared on all fronts for a “Red” nuclear attack and being able to survive in this underground secured territory, “where the resilient citizen could outwit a dangerous world with grit, skill, and moral determination.” With roots in the romanticized ideal of the settler-colonial foundations of the nation—the “Wild West” and the American dream—the underground frontier of the bunker as a means of survival appealed to many Americans, who believed independence and resilience in the face of threat were core American values.

Promoting the survivability of nuclear war in fallout shelters was the public face of a far more thorough shelter effort to construct hardened facilities for military technologies and resources. In 1959, Cheyenne Mountain, outside of Colorado Springs, Colorado, was selected to house the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), the collaborative U.S.-Canada organization that provides aerospace warning, air sovereignty, and protection for North America. The location deep inside the Cheyenne Mountain Complex would protect NORAD’s system of computers in case of a nuclear strike. The burrowed complex remains one of the most famous icons of the Cold War in Colorado.

Communal Fallout Shelters in the Front Range and Denver Metropolitan Area

Weapons construction complexes and other military infrastructure located along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains put Colorado on the map as a potential target for missile strikes. The most notable risks to communities along the Front Range came from the proximity of Denver to the Rocky Mountain Arsenal and the Rocky Flats manufacturing facility, the proximity of Colorado Springs to the U.S. Air Force’s Cheyenne Mountain Complex, and important manufacturing and military operations in Fort Collins and Pueblo. The perceived risk associated with proximity to locations for potential missile strikes prompted local governments and municipalities to develop over one thousand shelters in the Denver metropolitan area alone, resulting in one of the highest numbers of communal shelters of any city in the United States.The National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program, implemented by the Kennedy Administration in 1961, funded an extensive survey of buildings to determine suitable shelter placement. Local governments hired local architectural and engineering companies to assess buildings in order to determine the feasibility of constructing public fallout shelter locations. These locations were then mapped, marked by signs and in community shelter plans, and occasionally stocked with survival supplies. Nathan Heffel, "Not That You'll Need Them, But You Can Still Spot Some of Denver's Fallout Shelters," Colorado Public Radio, August 15, 2017, http://www.cpr.org/show-segment/not-that-youll-need-them-but-you-can-still-spot-some-of-denvers-fallout-shelters/.A partnership between the federal government and state and local government agencies helped to maintain and keep records of these facilities.

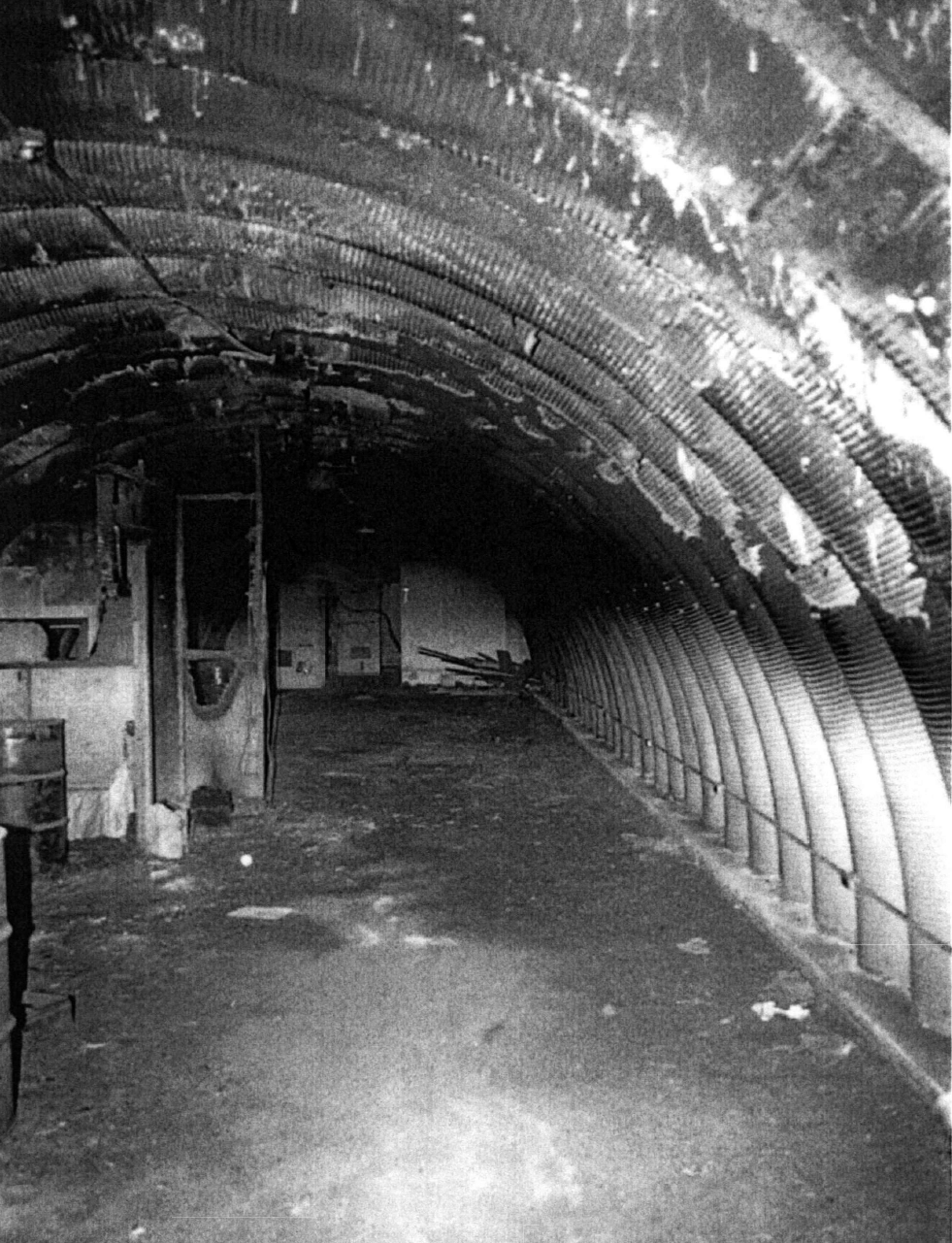

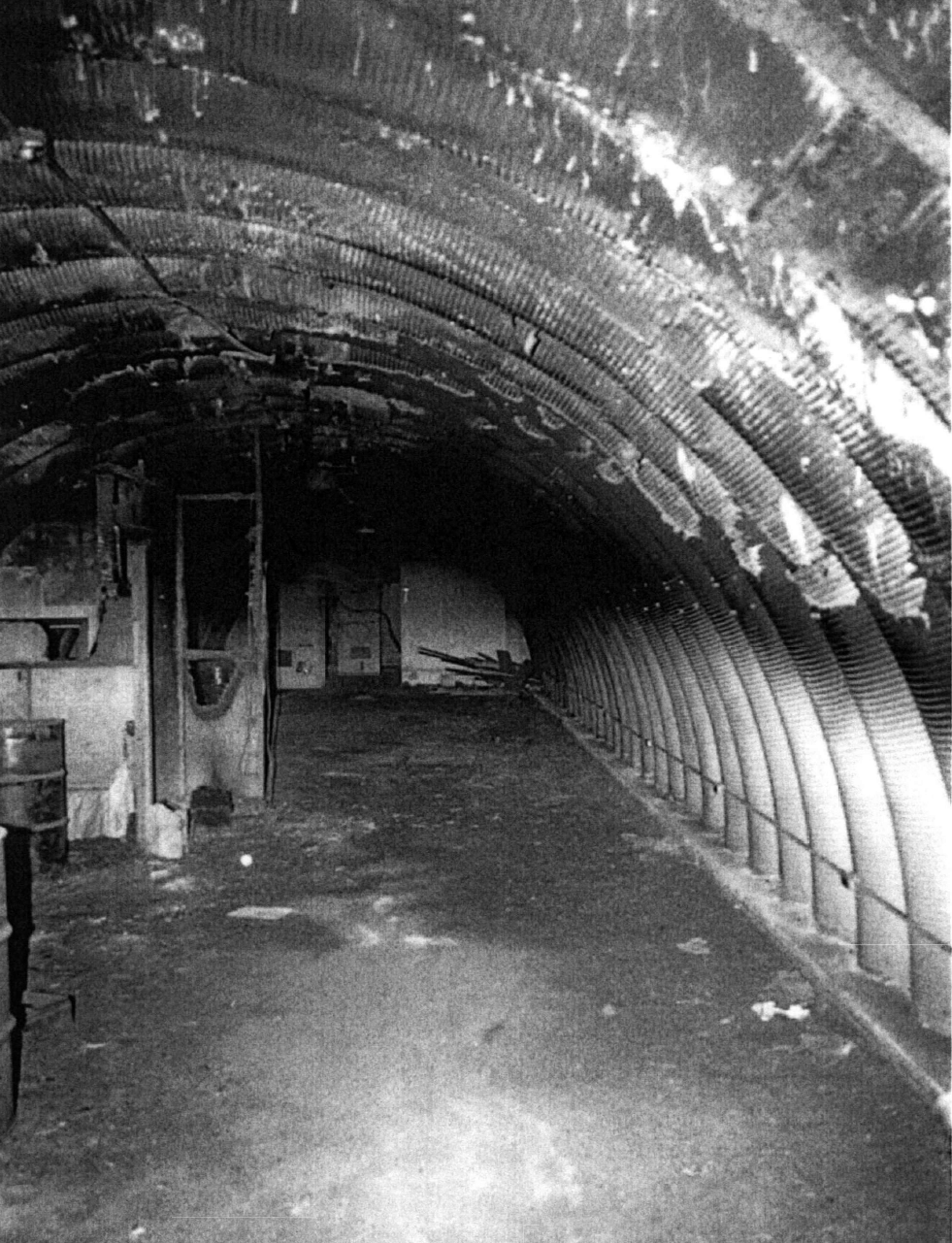

Karen Waddell, Interior of former Office of Civil Defense Emergency Operations Center at the Denver Federal Center, 1999, National Archives and Records Administration

The Denver Metropolitan area was one of the earliest communities in the country to plan community fallout shelters, and was well ahead of many cities when the Kennedy Administration implemented national measures for shelter establishment. Beginning in the early 1950s, the city developed a comprehensive civil defense plan and conducted an expansive survey of community buildings that identified 116 shelters. Thirteen of these shelters were stocked with food, water, blankets, and other survival supplies. Two prominent locations were the Denver City and County building, which could provide shelter for over 2,500 people, and the YMCA on Yale Avenue and Colorado Boulevard. Kathryn Plimpton, “The Forgotten Cold War: The National Fallout Shelter Survey and the Establishment of Public Shelters,” Master’s Thesis, Historic Preservation Program, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, April 24, 2015, https://digital.auraria.edu/work/ns/996bae38-fad0-4c85-b443-d7aceec21816.By 1964 the city of Denver had designated enough locations to provide shelter for over 900,000 people; 334 of these structures were officially demarcated with signage. Sarah Magnuson, “A Brief (and Bleak) History of Building Fallout Shelters in American Homes,” Apartment Therapy, July 10, 2020, https://www.apartmenttherapy.com/fallout-shelters-american-homes-36770210.Shelter buildings were made of stone, brick, or concrete and had the ability to hold 50-150 people for a duration of two weeks. More than 200 of Denver’s marked shelters were located in the downtown area. The number of suburban home family shelters built during this period, however, is poorly documented and difficult to estimate owing to a lack of historic records. Outside of Denver, the city of Golden identified 15 public shelters in existing buildings through the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program, and Arapahoe County similarly identified 6 shelters.

Media portrayals romanticize these shelters in war games and nostalgic memories of new American frontiers and patriotic duty. In reality, many shelters were little more than stark basements with few stocked food items or medical kits and only minimally suited to protect occupants from immediate post-blast fallout. In the event of a nuclear blast on the Front Range, shelter safety and effectiveness would have been hampered by poor access, uncertain supply lines, and lack of protection from radioactive fallout over substantial periods of time. Today, the lasting legacy of these shelters can be seen in the myriad household storage areas filled with forgotten boxes and the tattered remnant yellow and black signs on metropolitan buildings that point to basements long converted to other uses. Many family shelters were dismantled in the years following the relaxation of Cold War tensions; basement shelters were commonly repurposed or removed and filled in to promote safety.

Lasting Impacts

Fallout shelters and underground bunkers are still being built today. The current shelter industry ranges from small, homemade backyard shelters to large, elaborate luxury shelters built by engineers and contractors with access to massive private budgets. Culture around the underground shelter has shifted from the idea of a new American frontier and patriotism to doomsday preparations, anti-government sentiment, a resurgence of nuclear anxiety, and newer fears of climate catastrophe. In contrast to the Cold War era, home fallout shelters are no longer promoted by the government but are rather built as private safety precautions or out of fear of government collapse. The media has shifted from patriotic support of the family fallout shelter to reality television series, such as the Discovery Channel’s “Doomsday Bunkers” or National Geographic’s “Doomsday Preppers,” that showcase extreme or elaborate bunker setups. These backyard bunkers are neither small nor hastily constructed but are designed and built purposefully for long-term survival, with technical innovations that advance protection compared to the home fallout shelters of the 1960s. Modern fallout shelters often employ complex engineering techniques to determine suitable locations, depths, building materials, and filters, and to increase structural soundness and duration of protection. This renewed domestic homefront of environmental insecurity reveals the civic contradiction of earlier Cold War militarized domestic infrastructure. Ultimately, the patriotic ideal of mobilizing communal support for a nation under constant international threat may have concealed a deep-rooted American fear that personal hard work and preparation is the only way to outlive a time when situations are so dire that the government cannot be trusted to protect you.Sources

"A Look Back at America's Fallout Shelter Fatuation." CBS News, October 7, 2010. Accessed December 2, 2020.Heffel, Nathan. "Not That You'll Need Them, But You Can Still Spot Some of Denver's Fallout Shelters." Colorado Public Radio, August 15, 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Klara, Robert. “Cold War Nuclear Fallout Shelters Were Never Going to Work.” History.com, October 16, 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Magnuson, Sarah. “A Brief (and Bleak) History of Building Fallout Shelters in American Homes.” Apartment Therapy, July 10, 2020. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Masco, Joseph. "Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society." Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13-29. Accessed March 23, 2021.

Plimpton, Kathryn. “The Forgotten Cold War: The National Fallout Shelter Survey and the Establishment of Public Shelters.” Master’s Thesis, Historic Preservation Program, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, April 24, 2015. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Scoles, Sarah. “A Rare Journey into the Cheyenne Mountain Complex, a Super-Bunker That Can Survive Anything.” Wired, May 3, 2017. Accessed December 2, 2020.

“This Is Why Cheyenne Mountain Is One of the Most Secure Bases in the US.” Airman Magazine, July 23, 2020. Accessed December 2, 2020.

Continue on "Mobilization"